A Guide to Impact Enterprise

Social Enterprise, B Corp, Charitable business, Co-operative, Profit-with-purpose… What’s the difference? And does it matter? If yes… how and why?

Our friends at The Yunus Centre have developed the following fantastic guide in response to the growing interest in business being used as a force for ‘good’, and to help people navigate the diverse range of organisations who are doing it.

Beyond definitions and continuums, they want to help you distinguish between the various identities, motivations and models of ‘impact enterprise’, and appreciate that any given approach is highly dependent on context and purpose.

The Yunus Centre at Griffith University, use the term ‘Impact Enterprise’ to describe organisations that develop viable business models to achieve positive societal impact. As The Yunus Centre see it, the term ‘impact enterprise’ reflects a way of ‘doing’ business more than a type or form of organisation. As a result, organisations that ‘do’ impact enterprise can have very different ideologies, and operate with a range of different identities, goals, business models, and legal structures. They can also be found in nearly all geographies and sectors of the economy.

While this diversity should be celebrated (as it demonstrates that business can be used as a tool to create positive societal impact in nearly any context), the plurality of practice also confuses common understanding and frustrates consistent definition. It can also undermine the effectiveness of enabling policies and resourcing strategies, and create competitive tensions between actors who should otherwise be allies.

Going beyond the criteria and continuums often used to define, and differentiate between, impact-led businesses, this ‘guide’ takes a more nuanced look at the various characteristics, variables and applications of impact enterprise.

The aim is to assist policy makers, investors, practitioners, students, and other interested parties, to better navigate the plurality of this growing and dynamic field. The Yunus Centre hope to enable you to appreciate the influence of context, and differentiate between types of practice, without making binary, or simplistic distinctions, in respect to the comparable legitimacy of different approaches.

By broadening how we interpret the nature and diversity of impact enterprise, The Yunus Centre hope to improve debate and co-operation, and also the quality of strategies and criteria used to support impact enterprise, to determine investment and purchasing decisions.

The core properties of an impact enterprise

The core properties of an impact enterprise

While the rest of this guide explores the diversity of descriptors, strategies, choices and operational contexts that determine the sum characteristics of any given impact enterprise, there are some non- negotiable properties that all organisations engaged in doing impact enterprise share – namely, they trade for the primary purpose of creating positive outcomes for people, planet and places. The Yunus Centre propose that these properties are the overarching unifiers, and essential determinants of what is and isn’t impact enterprise.

Primary purpose can be evidenced by:

- An explicit purpose statement, constitution and/or a binding legal structure, alongside business strategies that are consistent with optimising the stated purpsoe.

- The majority of turnover being directly aligned with delivering the intended impact/stated purpose.

– And/or, the majority of profits being reinvested into activities aligned with the stated purpose.

– And/or the enterprise being democratically owned and governed by the community it was established to serve - Transparent reporting on what and how impact is being achieved (and for whom).

- Strategies to optimise (positive) and mitigate (negative) other social, cultural and environmental externalities resulting from operations.

Trading activity can be evidenced by:

- A viable and repeatable business model that trades goods, services and/or outcomes, on a financially sustainable basis.

*Some organisations mix business models with receipt of grants and donations, creating a blended-revenue approach to financing their activities. Receiving these revenues doesn’t exclude an organisation from being considered an impact enterprise as long as their trading activities, in themselves, are viable and sustainable. Typical ways that business models are mixed with grant / donations include stand-alone trading activities within a charitable or publicly funded operation (e.g. an animal welfare charity providing commercial veterinary services as part of its service mix), or taking on grants to deliver aligned services beyond core trading activities (e.g. a food-base social enterprise receiving grants to deliver education on nutrition in schools).

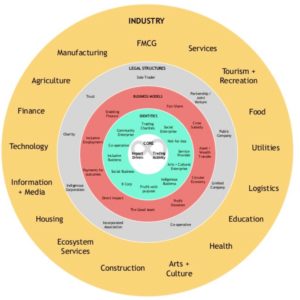

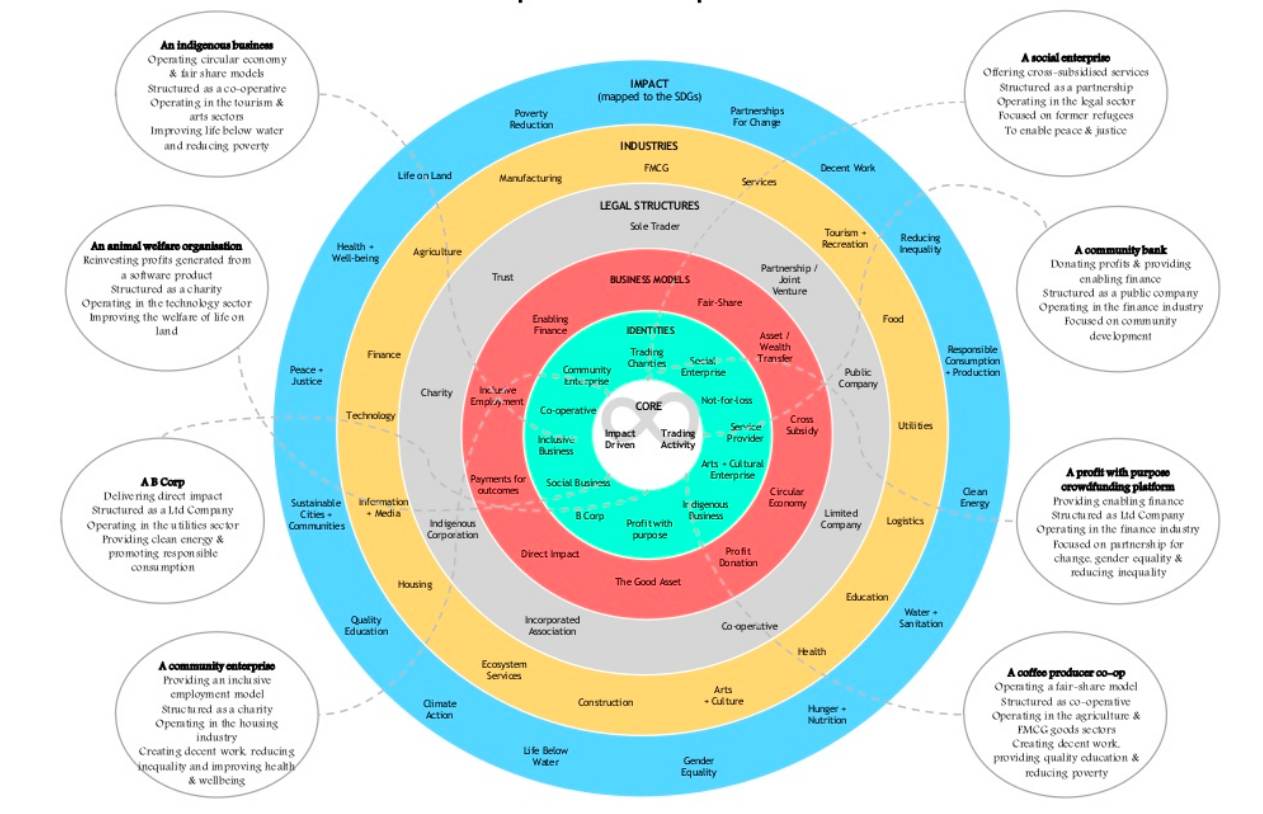

The diverse identities of impact enterprise

Business is a means to an end. With impact enterprise, the end is creating positive societal impact. However, beyond this primary goal, impact enterprise is initiated by individuals, collaboratives and organisations with myriad interests, ideologies, motivations, and missions. These drivers create very different identities – forming a range of descriptors, categories, cultures and movements under the broad umbrella of impact enterprise.

Business is a means to an end. With impact enterprise, the end is creating positive societal impact. However, beyond this primary goal, impact enterprise is initiated by individuals, collaboratives and organisations with myriad interests, ideologies, motivations, and missions. These drivers create very different identities – forming a range of descriptors, categories, cultures and movements under the broad umbrella of impact enterprise.

Identities can be determined by certification, definition, cultural origin, self-assertion, geography, core practice, the directive of a movement leader, or legal structure. Some identities under the umbrella are proudly business-first (e.g. ‘profit with purpose’ businesses). Others subordinate the commercial aspects of their operation in preference for descriptors emphasising their mission (e.g. ‘arts collective’ or ‘charity’).

Some organisations hold multiple identities, leading them to be categorised in different ways depending on context. The breadth and fluidity of these various identities can create confusion for customers, investors, and supporters, alike, because they are not necessarily comparable or consistent. For example, charities and social enterprises are often grouped as different entities, either due to how they self-identify or because of different underlying legal structures. However, social enterprises can also be set up using charitable legal structures, and may identify with one, or both, descriptors. Tricky.

Differences in identity can provoke frustrating debates about legitimacy of approach while obscuring commonalities of intent. As a result, while identities are very important for lots of reasons, they are less helpful for determining who is, or is doing, impact enterprise. For this reason, when designing policies, strategies and support facilities, focusing on the fidelity of purpose and materiality of impact, is likely to offer more reliable criteria than categorisation by identity – what they do is more important than who they are.

Blended value can be created in many ways

The critical function of impact enterprise is being able to create social, environmental and / or cultural value while also generating revenue. While these objectives are often seen as trade-offs, there are a number of ways they can work in tandem – creating ‘blended value’. Some organisations combine multiple blended business models within their operations to increase their overall impact.

Some examples of blended business models (as The Yunus Centre describe them):

Some examples of blended business models (as The Yunus Centre describe them):

Profit donation – these business models may not create any direct impact themselves but donate / reinvest their profits to resource impact-orientated activities. Australian example: Humanitix

Cross subsidy (one-for-one) – customers buy a product or service and an equivalent product is donated to someone in need. Australian example: Clearly

Circular economy – enterprise creates new value by recycling, repurposing or regenerating materials and / or natural resources. Australian example: Substation 33

The good asset – productive assets managed to generate public goods and also generate revenues that can be reinvested into impact projects and / or community development. Australian example: Hepburn Wind

Direct impact – delivering innovative products or services that address market failures and create positive impact, often with the potential to scale. Australian example: Nightingale

Inclusive employment – enterprises that train and/or employ people who experience barriers to work for a variety of reasons. Australian example: Good Cycles

Fair share – economic benefits (and decision-making) are distributed equitably within an enterprise and/or supply chain. Australian example: Food Connect

Payments for outcomes – the enterprise is able to attribute and verify the value of the outcomes they deliver and receive payments (usually from a government or philanthropic counterparty) based on their performance. Australian example: Newpin

Enabling finance – facilitating access to finance and resources for other impact-driven organisations and initiatives. Australian example: PledgeMe

Asset / wealth transfer – generating and transferring assets and/or wealth to disadvantaged groups or communities. Australian example: The Cape York Partnership

Impact enterprise can be done using many legal structures

Impact enterprises can be set up/delivered through a wide range of legal structures – you don’t have to be a company to do business, and you don’t have to be a charity to create impact.

Impact enterprises can be set up/delivered through a wide range of legal structures – you don’t have to be a company to do business, and you don’t have to be a charity to create impact.

The legal form that any given organisation adopts engenders different benefits and constraints – e.g. an impact enterprise adopting a charitable legal form will be able to access philanthropic support but won’t be able to distribute profit or raise capital by selling equity. As we’ve seen, sometimes a chosen legal structure shapes identity and stakeholder perceptions. Some legal forms, such as co- operatives, have deep implications for governance and decision making.

It is essential to make sure the legal form is compatible with the goals and operational context of the business approach – ideally the legal form(s) should be determined after the purpose and business model are decided, or at least in tandem.

Many impact enterprises adopt multiple legal forms to enable and safe-guard different aspects of their operations. Increasingly, specialised legal structures, such as Community Interest Companies and B Corporations, are being established by governments that want to grow impact enterprise in their jurisdictions.

Impact enterprise can be done in any sector or industry

Impact enterprise is being done in nearly every sector of the economy. While the sector of business activity will always have implications for how impact can be created, it doesn’t necessarily determine the nature of the impact – e.g. an impact enterprise operating in the food industry may be focused on using its business to create employment opportunities for young people who have dropped out of education.

Impact enterprise is being done in nearly every sector of the economy. While the sector of business activity will always have implications for how impact can be created, it doesn’t necessarily determine the nature of the impact – e.g. an impact enterprise operating in the food industry may be focused on using its business to create employment opportunities for young people who have dropped out of education.

That said, many of the impact enterprises using a ‘direct impact’ model will focus on tackling an aspect of market and / or systems failure within their chosen industry. Examples of this include impact enterprises that innovate around the affordability and sustainability of housing, or increasing access to quality health care.

Areas of societal impact

There are many areas where a positive impact can be made. The SDGs articulate a cohesive, high-level framework of all things we need to get right if we are to thrive as a species, and as a planet. Impact enterprises often concentrate on tackling specific issues/areas of impact, although some are able to create benefits in multiple areas. All should aim to mitigate any negative externalities in areas outside their primary focus – i.e. being carbon neutral while focusing on education.

There are many areas where a positive impact can be made. The SDGs articulate a cohesive, high-level framework of all things we need to get right if we are to thrive as a species, and as a planet. Impact enterprises often concentrate on tackling specific issues/areas of impact, although some are able to create benefits in multiple areas. All should aim to mitigate any negative externalities in areas outside their primary focus – i.e. being carbon neutral while focusing on education.

The focus of impact can also have an effect on business viability. Where markets (generally) work, it is easier to grow a scalable enterprise – i.e. solar panels. Where markets fail, or don’t exist, such as responses to domestic violence, finding a viable business model can be difficult and usually needs to work tangentially – e.g. using a ‘profit donation’ model to resource a dedicated service.

The diverse movement of impact enterprise

The sum is greater than the parts

It is impossible not to recognise the interdependence of all the impact areas articulated by the SDGs. Together they provide the life-giving environment and the social foundations that humans need to thrive. These elements are not trade-offs with economic development, they are interdependent parts of it, and necessary enablers for long-term prosperity.

It is impossible not to recognise the interdependence of all the impact areas articulated by the SDGs. Together they provide the life-giving environment and the social foundations that humans need to thrive. These elements are not trade-offs with economic development, they are interdependent parts of it, and necessary enablers for long-term prosperity.

The ‘impact economy’, at its simplest, is an economic system which accounts for, and prioritises, a broader range of value creation and destruction – the true value of externalities and stocks that will determine a safe and viable existence for our present and future civilisations.

To transform our economy at the meta-level, we will require more organisations to become impact enterprises at the micro and meso-levels, regardless of their size, identity, legal structure, geography, or industry. In this respect, impact enterprise represents a new paradigm, and a diverse movement, that needs widespread understanding, adoption and amplification across all sectors of society and the economy.

About Griffith Centre for Systems Innovation

Formerly The Yunus Centre, Griffith University, the Griffith Centre for Systems Innovation is working to grow capabilities and infrastructures to accelerate shifts towards regenerative and distributive futures. Part of Griffith Business School in Logan, SE Qld, it rehearses on a local scale, ideas that may be of interest at a global scale.

No Comments